Khroul V. Religious agenda in Russian mainstream media: trends and controversies

УДК 316.77:2-14

RELIGIOUS AGENDA IN RUSSIAN MAINSTREAM MEDIA:

TRENDS AND CONTROVERSIES

Khroul V.

The lack of understanding by journalists of the religious life complexity and sensitivity, the difference between profane and sacred leads to dysfunctions in the reporting on religions. Content analysis of the most popular Russian mainstream media discovered the marginalization of texts about religion in the general information agenda of Russian mass media, with the dominance of Orthodox Christianity in journalistic texts and the underexposure of religious minorities, while the popular presentation of doctrinal matters remains in media minimal. In addition, a “crisis of experts” in publications on religious topics has been detected: journalists prefer to seek comments from officials and public activists more often than from religious scholars. The “conflict of formats” in media and religions, the mismatch of mutual perceptions of the boundaries of permissible and acceptable in the secular media and religious communities remains an important characteristic of the current state of media-religion relations in Russia.

Keywords: religion, Russia, media, agenda, minorities, experts.

РЕЛИГИОЗНАЯ ПОВЕСТКА ДНЯ В РОССИЙСКИХ СМИ:

ТЕНДЕНЦИИ И ПРОТИВОРЕЧИЯ

Хруль В.

Непонимание журналистами особой сложности освещения религиозной жизни, соотношения в ней религиозного и светского, личного и общественного, профанного и сакрального приводит к конфликтам между последователями религий и журналистского сообщества. Контент-анализ наиболее популярных российских СМИ позволил автору выявить маргинальность текстов о религии в общей информационной повестке российских СМИ, причем при доминировании в журналистских текстах православной тематики и "недоэкспонировании" религиозных меньшинств популярное изложение догматической сути религиозных вероучений остаётся минимальным. Кроме того, обнаружен "кризис экспертов" в публикациях на религиозную тематику: журналисты предпочитают чаще обращаться за комментариями к чиновникам и общественным деятелям, чем к религиоведам.

Ключевые слова: религия, Россия, СМИ, повестка дня, меньшинства, эксперты.

Funded by the EU NextGenerationEU through the Recovery and Resilience Plan for Slovakia under the project No. 09I03-03-V01-00088.

Introduction

Knowledge of the social nature of religion, channels of its mediatisation and forms of functioning in the public sphere is necessary for adequate coverage of religious issues in the media. Often the lack of understanding of the special complexity of the religious life, the controversies between religious and secular, profane and sacred lead to conflicts between followers of religions and the journalistic community [q.v.: 4; 5; 6; 10; 11]. The wish of religious organizations to make a serious impact on media policy (numerous religious initiatives aimed at banning certain films, books and theatrical performances) and to correct media agenda add tensions to the conflict.

Due to its fundamental traditionalism, dogmatism, hermetic nature religion differs from other social subsystems by a special language, specific, difficult to decode forms of manifestation [7; 14; 18], internal dichotomy of sacred and profane [19; 20]. For journalists, it is much easier to cover sports, culture, economy or politics rather than religion.

A study of the coverage of religious life by Russian media was conducted by the author of this article in 2018, in a stable media system, even before the turbulent whirlwinds of the Covid-19 pandemic and military conflict. It is important to note that the results of the study have not been published before and are of significant value for understanding media policy in the field of religious life coverage at present.

Sources of information, volume of attention, subject of coverage

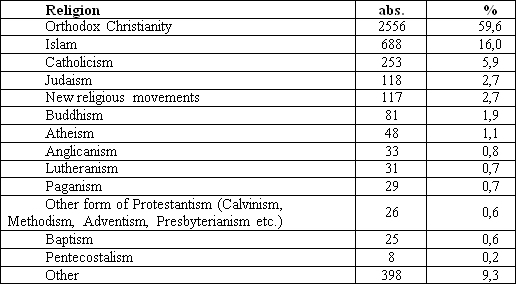

We conduct the content analysis of 4,291 texts published between April 1, 2017 and March 31, 2018 in the 25 most popular Russian media outlets. The research proved that Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) is the leader in terms of the volume of media attention to various religions (59.6%). It is followed by Islam (16.0%), and of the other religions, only Catholicism has a mention rate of more than 5%, which is presumably related to the activities of the Pope and some borrowed holidays, such as Halloween or Valentine’s Day, that are gaining popularity, as well as recent scandals related to sexual abuse in church structures. The findings are presented in more detail in Table:

Amount of media attention to different religions (in % of the total number of texts,

N=4291, sum exceeds 100%, up to and including three religious communities

were noted when coding during the content analysis)

The ROC enjoys significant influence in shaping the media narrative around moral, ethical and spiritual issues, while the government uses religious themes to promote traditional values, patriotism, and national unity.

One of the most consistent themes in Russian mainstream media is the portrayal of the ROC as a central pillar of Russian national identity and cultural heritage. This narrative positions Orthodoxy as not just a religion but as the spiritual and moral foundation of the Russian state and people. Media outlets frequently emphasize the Church’s role in the preservation of Russian language, traditions, and values, contrasting these with the influence of Western liberalism and secularism.

The close relationship between the ROC and the Russian government is frequently highlighted in the media, reinforcing the idea of synergy between religious and state institutions. Russian media often features Patriarch Kirill, the head of the ROC, in high-profile events with President Putin. These events include joint appearances at religious celebrations, public prayers, and state ceremonies, symbolizing the unity of Church and state. Putin is often portrayed as a defender of Orthodoxy, and the media highlights his attendance at religious services, reinforcing his image as a leader who supports and is supported by the Church.

Russian mainstream media frequently uses religious figures, particularly Orthodox clergy, as moral authorities on social and ethical issues. The ROC’s views on morality are often presented as a counterbalance to the perceived moral decline of the West.

The Church regularly provides commentary on a range of social issues, such as drug addiction, alcoholism, family breakdown, and abortion. These issues are framed in moral terms, with the Church offering guidance and solutions based on Orthodox teaching. Media outlets often feature clergy discussing these topics, promoting the idea that spiritual solutions are crucial for addressing societal problems.

A recurring theme in Russian media is the critique of secularism and liberalism, often presented as the root of various social ills, both domestically and internationally. This criticism aligns with the religious agenda of promoting Orthodoxy as the foundation of a morally healthy society.

In the media agenda, after Orthodox Christian domination, a significant number of texts cover Islam (16%). State-aligned media often highlight Islam’s role as a “traditional” religion, portraying Muslims as loyal citizens contributing to Russia’s multicultural and multi-religious identity. For example, Islamic holidays like Eid al-Adha are covered in a generally respectful manner, with the media emphasizing peaceful coexistence between Muslims and Orthodox Christians. However, the portrayal of Islam is often overshadowed by a focus on radicalization and terrorism, particularly in the context of the North Caucasus or Chechnya. Media narratives tend to conflate Islam with potential security threats, especially in the context of Islamic extremism or foreign influences from the Middle East. This leads to the media frequently discussing Islamic groups through the lens of law enforcement, counter-terrorism, and surveillance.

Judaism is one of the officially recognized religions in Russia, and the media generally covers Jewish communities in a neutral or positive light.

Media coverage of Buddhism tends to be neutral or positive, often focusing on cultural and ceremonial aspects. Reports on Buddhist holidays or events, like Losar (Tibetan New Year), emphasize peaceful coexistence and the contribution of Buddhism to Russia's cultural diversity. Buddhism is often marginalized in Russian media, receiving far less coverage than Islam or Judaism. When it is featured, it is typically in a non-political context, focusing on heritage, tourism, or spirituality.

Groups such as Catholics, Protestants, and Old Believers receive varying degrees of coverage, often shaped by their historical relationships with the state and the ROC. “Non-traditional” or “New” religions communities such as Jehovah’s Witnesses (an extremist religious organization banned in the Russian Federation), Scientologists (the organization’s activities are considered undesirable in the Russian Federation), and various other new religious movements are frequently portrayed in a negative light, often framed as threats to social cohesion or as foreign sects.

The Roman Catholic Church has a small presence in Russia, and its portrayal in the media is often shaped by its historical tension with the ROC. The media sometimes covers Catholic holidays like Christmas (celebrated on December 25th) and events involving the Vatican, but such coverage tends to be framed in a way that reinforces the primacy of Orthodoxy. For example, the Pope’s statements may be acknowledged, but always with a note of difference or distance from the Russian Orthodox perspective. Media narratives cast the Catholic Church as a representative of foreign values, contrasting it with Russian Orthodoxy’s rootedness in Russian culture.

Protestant groups, including Evangelicals, Lutherans, and Baptists, receive little attention in the mainstream media, and when they do, the coverage is often negative or framed in a suspicious light. Protestantism is often associated with Western influence, and media reports sometimes portray Protestant communities as being connected to foreign missionary activity. This aligns with broader narratives that depict Western religious groups as undermining Russian traditions or attempting to convert Russians away from Orthodoxy. Certain Protestant groups have been targeted by restrictive laws, which limit missionary work and religious gatherings. The media’s coverage of these restrictions tends to focus on law enforcement, framing the state’s actions as necessary to protect social order and prevent the spread of “foreign sects”.

Old Believers, a group that split from the ROC in the 17th century over liturgical reforms, are sometimes covered in a neutral to positive light, especially in historical or cultural contexts. However, they remain marginalized compared to the mainstream ROC, with their practices sometimes described as outdated or rigid.

When it comes to unexpected findings, 398 texts contain references to various spiritual practices – outside of mainstream religions. Therefore deserve a special attention for further analysis.

Religious activities themselves (26.6%) in media texts are less presented, than institutional and interreligious interaction (39.2%), i.e. publications are mainly devoted to the social aspects of the institution's activity rather than to the dogmatic essence of doctrine:

Subject of publication in religious texts (in % of the total number of texts, N=4291,

sum exceeds 100%, up to three options are possible)

On the one hand, we see the limits the access of a wide audience to religious meanings and values. At the same time, with the emergence and rapid development of the Internet, religious organizations themselves have gained broad opportunities for direct or indirect contact with the audience to meet its interests and needs.

In 87.7% of materials journalists act as outside observers. On the one hand, this testifies to the minimal immersion of media employees in religious life, and on the other hand, journalists do not consider themselves as experts in the field.

Author’s role in relation to the story being described

(in % of the total number of texts, N= 4291)

The main format of texts on religious topics, which does not imply an active role of the journalist in the events. In general, the principle of neutrality and distance is becoming more and more widespread in Russian journalism, which is also reflected in the coverage of religious life.

More than 55% of materials do not contain a “hero” as an active subject at all, and only one fifth of them position a religious figure as such. The low representation of experts and religious scholars in media texts (1%) on religious topics is also surprising and needs additional analysis, while officials, representatives of the authorities and the public together appear as acting subjects in 16.3% of texts. So, media discourse on religion in Russia is authorities oriented rather than experts oriented.

Heroes of the publication in religious texts

(in % of the total number of texts, N=4291)

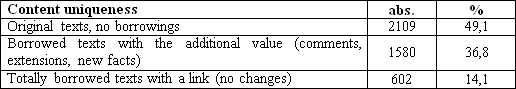

As for the uniqueness of texts covering religious life, more than half of the materials are either based on publications of other media or are completely borrowed from them. A deeper analysis of the texts claiming to be original shows that in fact they contain hidden borrowings, but without references. At the same time, the number of borrowed but commented and supplemented texts (36.8%) indicates the journalists' desire to enlighten the audience by providing it with new information that they consider relevant to the public’s interest.

Degree of uniqueness and independence of content

(in % of the total number of texts, N= 4291) of religious texts

(in % of the total number of texts, N=4291)

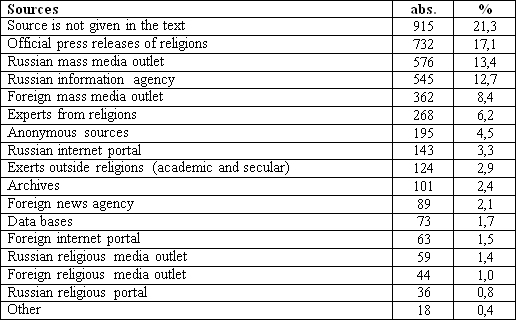

Finally, another important characteristic of publications about religion in the Russian media is the source of information. And here the results are unexpected – in one fifth of the publications (21.3%) the source of information is not indicated at all and is not even identified from the text.

Sources of religious information used by the author of the text (in % of the total

number of texts, N=4291, the sum exceeds 100%, several references to different

sources are found in the texts)

This indicator not only testifies to the quality of journalism and compliance with professional standards, but also reveals the potential risks for both – the media and the audience. Media without sources and fact-checking become instruments of distortion of the real picture of the world, disinformation, and mythologization of religion, and the audience without the source is left with very limited opportunities to verify the facts contained in the publication.

Press releases, reports, and official statements by religious representatives (17.1%) are the leading source of information, outstripping all others, which reveals the reactive rather than pro-active nature of contemporary Russian journalism (at least in the coverage of religious topics), i.e. journalists do not search for topics, do not initiate them, but wait for press releases and put themselves in the position of hostages of an agenda formed without their participation. Next in the descending list of sources various Russian and foreign media are located, while religious leaders themselves (6.2%) and religious experts (2.9%) are approached by journalists much less often. That is, direct information, commissioned from first-hand sources and competent experts, appears in the texts secondary to indirect information, obtained from other media and most often published without additional verification.

Media event with Saint Nicholas relics: pride and doubts

The phenomenon of media events in the religious sphere is important to look more attentively on possible communicative strategies of the media and religious communities.

The promotion of religious events and pilgrimages is another key element of the religious agenda in Russian media. Media often covers the arrival of Orthodox relics in Russia, promoting pilgrimages to venerate them. For instance, the arrival of the relics of Saint Nicholas in 2017 was widely covered, with media portraying it as a major spiritual event for millions of believers. Such coverage reinforces the importance of faith in daily life and promotes the idea that Russia is a holy land for Orthodox Christianity.

In 2017 the relics of St. Nicholas were brought to Moscow from Bari (Italy) they were in Russia for 69 days, 53 days in the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow. In early July the relics were delivered to the Alexander Nevsky Lavra in St. Petersburg. During its stay in Russia, the relics were worshipped by about 2.5 million people, which is the biggest act of veneration for many years [3; 9]. The scale of the pilgrimage and its attractiveness provoked journalists and media managers to present it as a media event in hope to gain bigger audiences.

The media coverage was extensive, ranging from religiously focused reports to broader public interest stories about the pilgrimage of millions of Russians. Many outlets presented the transfer of the relics as a moment of national religious revival, emphasizing the deep connection between Saint Nicholas and Russian Orthodoxy.

“Russia-24” and “Channel One” highlighted the event as a symbol of the growing influence of Orthodox Christianity in Russian society. The media portrayed the arrival of the relics as a sacred occasion for millions of believers, aligning it with the broader narrative of religious revival in post-Soviet Russia. RT (“Russia Today”) and “Izvestia” noted the importance of the relics for Russia, calling Saint Nicholas the “Protector of Russia” and underlining the historical and spiritual ties between the saint and the Russian people. State-run TV networks often broadcast live footage from the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, showing Patriarch Kirill leading services in front of the relics.

Huge queues lined up to the relics, and the authorities even restricted traffic on Prechistenskaya Street in order to give free access the citizens to the Orthodox shrine [12]. Some orthodox bloggers asked the question: what caused such a rush? It was a well-known among Moscow Orthodox Christians, that only in Moscow the relics of the same Saint Nicholas are located in more than 25 churches, and one can get there easily, bypassing the queue [2; 15].

The media campaign was huge and massive. According to the daily poll “VTsIOM-Sputnik”, as a result of media campaign, more than three quarters of citizens (81%) knew about this event, and more than two thirds of respondents (72%) expressed their desire to venerate the relics personally to the relics. “In this case, we can speak of an event of great significance for the Orthodox, the entire Russian society. The interest and respectful attitude testify not only to the degree of the Russians’ churchgoing, but also to the desire to unite around the values underlying Christian teaching. Worship of the relics is a manifestation of respect for the spiritual feat of the saint and an appeal in the hope of help. Obviously, this event will be one of the most significant this year,” said VCIOM expert Mikhail Mamonov [9].

The opinions around the relics expressed by the general public can be grouped into two polar opposite positions, which are presented below.

А. Standing in line is a pilgrimage. The first point of view was promoted by the head of the Synodal Information Department of ROC Vladimir Legoyda [1]. He recorded a special video, which was released on the TV channel “Tsargrad”, explaining why to stand in line to the relics. Legoida speaks negatively about those who consider it pointless to stand in line. Archpriest Andrei Boytsov, rector of the Patriarchal Court of St. Nicholas in Bari, also believes that standing in line is similar to pilgrimage: “Pilgrimage is a certain feat. If now pilgrims do not physically bear such labour as before, when they went to Bari for six months there and six months back on foot, at least people sacrifice some part of their income, because the trip is expensive, deny themselves something. The Church has never questioned that pilgrimage is very useful from a spiritual point of view for a believer. The same can be said about standing at the relics” [10].

Dmitry Filin notes in his blog that it is very important to bring labour and veneration to the saint. “This is useful primarily for us, but for the rest of society and for the authorities it serves as an indicator that the Orthodox are not an amorphous mass, far from the Church, but a force and a force to be reckoned with” – says the blogger [17].

Б. The queue to the relics is a planned PR campaign. Some Orthodox Christians consider that the bringing of the relics and making a media event was a PR action that misleads ordinary people.

The monk Theodorit (Senchukov) reminded: “In Moscow there are many temples in which the relics of St. Nicholas rest. But there are no such queues there. Why?” [16].

Archpriest George Mitrofanov, emphasizing the origin of the relics and the uneducated nature of people: “This idea that they have brought special relics, 'imported' relics, causes stereotypical reactions in many people, characteristic of their consciousness, far from Christian and cultural impact.” [13].

Generally, critical voices were located mostly in the Internet blogs and sites, but these reports were, however, relatively few compared to the overwhelmingly positive coverage in mainstream outlets. Mainstream media followed their agenda making accent on the national unity rather than the depth of the faith. The scale of the pilgrimage was emphasized, with TASS and “RIA Novosti” providing daily updates on the number of pilgrims. In Moscow alone, over 2.3 million people came to venerate the relics. So, numbers matter much more that other indicators [8].

Conclusion

The analysis of information sources, the volume of attention and subjects of coverage (in particular, religious media events), revealed in this paper, show the marginalization of this topic in the information agenda. Religion still remains on the periphery of attention of both journalists and media managers, since they do not see religion as a significant factor influencing the functioning of the media system. In addition, journalists' understanding of the peculiarities of the mediatization of religion in the media texts does not take into account the special sensitivity of the audience to coverage of religious events is an important element of professional culture.

The secular media, whose connection with the audience is weakening as they depend less and less on it economically (and more and more on the government and business), do not feel the market-driven need to broadcast religious value and normative models and, accordingly, address religious subjects in Russia sporadically and haphazardly, which naturally leads to the dysfunctions and conflicts described in this paper, exacerbated by the closed and hermetic nature of religions. The only exception is if the state asks its media to highlight some events, like the relics of Saint Nicholas in Russia.

The portrayal of religious minorities in Russian mainstream media, is shaped by a combination of state priorities, cultural narratives, and the dominant role of the Orthodoxy. While the ROC is often promoted as a central pillar of Russian national identity, other religious groups are frequently marginalized, misrepresented, or subjected to selective scrutiny. The media's approach to religious minorities reflects broader nationalist and patriotic themes, where Orthodoxy is emphasized as the core of Russian spirituality, while non-Orthodox religious groups are often framed as either tolerated or suspect, depending on their perceived loyalty to the state or alignment with official values.

Islam, Judaism and Buddhism, which are officially recognized as “traditional” religions alongside Orthodoxy. Media coverage of these groups tends to be more respectful, though still hierarchical, with Orthodoxy at the top.

The “conflict of formats” in media and religions, the mismatch of mutual perceptions of the boundaries of permissible and acceptable in the secular media and religious communities remains an important characteristic of the current state of relations between religion and mass media in Russia. While religions want to have their teaching more exposed and understandable for general public, the media agents (journalists, bloggers and influencers) prefer to follow ad-hoc curiosity and entertaining and scandalous agenda rather than discover complicated and problematic issues. Therefore the mutual distrust between media and religious institutions are still high.

Bibliography:

1. Владимир Легойда: Зачем стоять в очереди к мощам святителя Николая? [Web resource] // 29.05.2017. URL: https://goo.su/F5v9 (reference date: 01.10.2024).

2. Гладков П. Обман с привезенными мощами [Web resource] // Живой Журнал. Hueviebin1. 22.05.2017. URL: https://goo.su/8y9gOK (reference date: 01.10.2024).

3. Головко О. Как готовят мощи святителя Николая для принесения в Россию [Web resource] // Правмир. 10.05.2017. URL: https://goo.su/J52fk24 (reference date: 01.10.2024).

4. Легойда В.Р. Религиозный дискурс в современных СМИ: можно ли говорить о христианстве в эпоху секуляризма [Web resource] // Русская народная линия. 01.06.2006. URL: https://goo.su/eT6sY (reference date: 01.10.2024).

5. Лученко К.В. Интернет и религиозные коммуникации в России [Web resource] // Relga. 2008. № 12. URL: https://goo.su/U3UGeFm (reference date: 01.10.2024).

6. Малухин B.H. Русская Церковь, светские СМИ и христианские ценности в постсоветской России // Церковь и время. 2006. № 2. С. 207-214.

7. Медиа накануне постсекулярного мира. Коллективная монография / Под ред. В.А. Сидорова. СПб., Петрополис, 2014. 176 с.

8. Мощи Николая Чудотворца вернули в Италию [Web resource] // РБК. 29.07.2017. URL: https://goo.su/oX7Uhh (reference date: 01.10.2024).

9. Мощи Николая Чудотворца: первая неделя в России [Web resource] // ВЦИОМ. 26.05.2017. URL: https://goo.su/Swz3Tjx (reference date: 01.10.2024).

10. Островская Е.А. Интернет-медиатизация исповеди в среде сетевых православных VK.com сообществ // Logos et Рraxis. 2018. T. 17. №. 3. С. 45-58.

11. Островская Е.А. Медиатизация православия – это возможно? // Мониторинг общественного мнения: Экономические и социальные перемены. 2019. № 5. С. 300-319.

12. Перекрытия и ограничения движения в связи с организацией доступа граждан к православной святыне ‒ частице мощей Святителя Николая [Web resource] // Mos.ru. 20.05.2017. URL: https://goo.su/cODXu (reference date: 01.10.2024).

13. Протоиерей Георгий Митрофанов: Мы подходим к мощам со страхом шаманиста [Web resource] // Правмир. 03.07.2017. URL: https://goo.su/xvSlTA (reference date: 01.10.2024).

14. Религия в информационном поле российских масс-медиа. М., 2002; Религия и конфликт / Под ред. А. Малашенко, С. Филатова. М: Медиасоюз. Гильдия религиоз. журналистики, 2003. 142 с.

15. Титко А. Где находятся мощи Николая Чудотворца в Москве [Web resource] // Комсомольская правда. 10.07.2017. URL: https://goo.su/732elEX (reference date: 01.10.2024).

16. Три священника про очередь к мощам святителя Николая [Web resource] // Правмир. 31.05.2017. URL: https://goo.su/r2ZEKg (reference date: 01.10.2024).

17. Филин Д. Несколько слов по поводу принесения святых мощей свт. Николая Чудотворца из Бари [Web resource] // Живой Журнал. Filin_dimitry URL: https://goo.su/FkugqNE (reference date: 01.10.2024).

18. Щипков А.В. Религиозное измерение журналистики. М.: Пробел-2000, 2014. 270 с.

19. Religion and media / Еd. by De Vries H., Weber S. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. 649 p.

20. The power of religion in the public sphere / Еd. by Mendieta E., Van Antwerpen J. New York: Columbia University Press, 2011. 128 p.

Data about the author:

Khroul Victor – Doctor of Philological Sciences, Visiting Researcher at Catholic University in Ružomberok (Ružomberok, Slovakia).

Сведения об авторе:

Хруль Виктор – приглашенный исследователь Католического университета в Ружомбероке (Ружомберок, Словакия).

E-mail: victor.khroul@gmail.com.