Khrul A., Khroul V. Humour in media discourse on religion as a factor of conflict

УДК 070:316.482:2

HUMOUR IN MEDIA DISCOURSE ON RELIGION

AS A FACTOR OF CONFLICT

Khrul A., Khroul V.

Humour is located in the sensitive areas of the two basic human freedoms: the freedom of expression and the freedom of belief. The paper is focused on humour in media discourse on religion as a factor of conflict and examines important factors underexposed. According to the results of the pilot project, conducted in Russia, the approaches and attitudes towards humour as a well as a will for compromise and consensus differ in Orthodox Christian, Muslim, Jewish, Catholic and Protestant communities. Authors suggest the mapping the “zone of mutual responsibility” of journalists and religious leaders will lead to elaborating the “pact on humour” between them. For the future research authors propose to analyse the religious and ethnic factors in the formation of a sense of humour and culture of laughter in general in order to have more detailed picture on strictly religious sensitivity towards humour.

Keywords: humour, religion, media, conflict, journalism, Orthodox Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Catholicism, Protestantism.

ЮМОР В МЕДИАДИСКУРСЕ О РЕЛИГИИ

КАК ФАКТОР КОНФЛИКТА

Хруль A., Хруль В.

Юмор находится в чувствительной и в некоторых случаях конфликтной зоне взаимодействия двух основных человеческих свобод: свободы слова и свободы вероисповедания. Статья посвящена юмору в медиатекстах о религии как факторе конфликта. Согласно результатам пилотного проекта, проведенного в России, подходы и отношение к юмору, а также стремление к компромиссу и консенсусу различаются в православных, иудейских, исламских, католических и протестантских общинах. Авторы предполагают, что составление карты «зоны взаимной ответственности» журналистов и религиозных лидеров приведет к разработке «пакта о юморе» между ними. В качестве будущего исследования авторы предлагают проанализировать религиозные и этнические факторы в формировании чувства юмора и культуры смеха в целом, чтобы иметь более подробное представление о сугубо религиозной чувствительности к юмору.

Ключевые слова: юмор, религия, медиа, конфликт, журналистика, православие, ислам, иудаизм, католицизм, протестантизм.

Introduction

On 16 October 2020, a French teacher was beheaded in a Paris suburb after showing controversial cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad to some of his pupils. Two similar attacks within two weeks enforced the French President to increase the security at places of worship and schools across France. Macron’s suggestion on the “Islamist terrorist attack” caused a national debate about blasphemy and deepened divisions over the secular identity of the country [10].

On September 7, 2021, the Byelorussian state newspaper Minskaya Pravda published a caricature of Catholic priests using a swastika. The cartoon showed a priest wearing a swastika in place of a pectoral cross, with Belarus’ banned red-white national flag under his arm, singing the anthem “Magutny Bozha” (O God Almighty) [q.v.: 20].

Yuri Sanko, a spokesman for the Catholic Church in Belarus, said that the newspaper “spits in the face of millions of Catholics living in our country”. “If you look at the caricature on the front page, where the cross is profaned, in my opinion, it is an insult to all Christians, a propaganda of Nazi symbolism”, stated the priest [20].

Humour in its broad sense, including irony, sarcasm, satire, grotesque is an important reflective and critical tool of culture, and therefore it is widely represented throughout history. The proposed study is focused on the important subsystems of culture, religious and one of the most influential processes in modern culture – the process of mediatization.

Humour is located in the sensitive areas of the two basic human freedoms: the freedom of expression and the freedom of belief. The conflict provoked by the Danish cartoon scandal became a battle of two camps. On the one side, Muslims mostly, with the occasional support of non-Muslim intellectuals, or even Jewish and Christian influent leaders, have denounced it as scandalous and demanded that unconditional respect be given to the figure of Mohammed. The others, invoking freedom of expression which is untouchable and non-negotiable, claimed the right to mock any figure of the sacred, including that of God himself.

Religious doctrines are fundamentally “serious”, dogmatic and non-doubtful, their critical rethinking (sometimes humorous) faces angry reactions. Each religion has its own area of the sacred, making jokes on the sacred is strictly tabooed (in the Russian law it is codified as “insulting the feelings of believers”). However, religious practices and religious life is not reducible to the sacred, there is room for different points of view, discussions, arguments, and, consequently, humour. The content area of making jokes in different religions has a different size (obviously in Judaism it is larger than in Islam, however, this still needs to be empirically proven) and a different set of tools (in some religions images are forbidden, for example).

A detailed description of the boundaries, the limits of acceptable, tolerated humour often remains unarticulated in religions themselves, consequently, it is almost unknown for media. Vise versa, the “logic of media” in many cases is not understandable (and therefore – unacceptable) for religious leaders. This contradiction, located between the freedom of speech and the freedom of faith, causes a deep (perhaps the deepest) conflict in the mediatization of religion. And this is the main research problem of the proposed project.

From one side, in-depth analysis of humour limitations in different religions promises to equip journalists and politicians with an effective tool for remapping the field and get a visible demarcation line, potentially conflictual if crossed. From another side, it will expose the limitations for religious dictatorship and authoritarian demands towards the freedom of speech for journalists and politicians in the public sphere.

The proposed project is also a call for the academia and policymakers to take seriously into consideration the underexposed and underestimated “humour” factor of faith-based conflicts and tensions that have become so visible during the last decades.

Religion, humour and media: theoretical frameworks and empirical studies

Why are religious people so sensitive when it comes to jokes, cartoons and parodies? How do humour, religion and media interact? Although the importance of humour both in and for religions is recognized, it has rather rarely been studied in academia. Scholars from different fields have explored humour in Biblical texts [q.v.: 13], in the life of Christ and the saints, and in religions other than Christianity [q.v.: 12; 14]. Some interesting works have been published on the functions of humour in religion from an anthropological and sociological perspectives [q.v.: 6; 8; 9; 11; 22; 23; 25]. There are also recent theoretical attempts to valorise positive links between the comic and religion from a theological, religious, or spiritual point of view [q.v.: 7; 12; 15; 18; 19; 21]. In of different religious communities on offensive humour became a subject of substantial scholarly discussion [7; 15; 17].

Nevertheless, the following questions are still underexposed. What is the meaning of humour in different religions? How does a religion respond to sarcasm and irony? Are there limits to mockery and making fun of what believers consider to be sacred?

Conflicts based on the opposition of humour and religion cannot be considered to be a unique phenomenon, they are rather only a particular case of more global problems: freedom of speech and self-expression, tolerance, and even the basic problem of “the other”.

The spreading of humour in modern (predominantly Western) societies and its more visible impact on the public causes conflicts based on the cases when humour is accused of an insult to the feelings of various social groups, primarily religious ones. Increasingly, jokes, memes, cartoons face protests of religious groups, leading to international scandals, criminal cases and even terrorist attacks.

Strengthening censorship and, as a result, self-censorship in relation to insulting believers’ religious feelings in many countries of the world does not seem to be an effective solution for the situation without in-depth analysis. After the Danish cartoon scandal in 2005-2006 journalists did not stop making laugh at things religious people consider to be sacred, and this misunderstanding led to the tragic terrorist act at Charlie Hebdo in Paris ten years later.

The analysis of social and cultural dynamics of humour and laughter in history and changes in the paradigm of the social attitudes humour [16] proved the complexity and multidimensional character of the phenomenon. A dispraise of laughter was more characteristic to the early medieval period, later on from the 12th century laughter began to be gradually accepted. The change in attitudes toward laughter and humour affected the whole society. A number of theological studies are devoted to searching the Bible for not only serious meanings but also glimpses of joyful laughter, irony, fun, as well as the comic side of famous biblical scenes. The results in these areas of theology indicate a huge potential in the rethinking of laughter and humour categories, as well as their integration into the modern religious worldview. However, religious institutions are more likely to preserve traditional attitudes.

In the context of Christianity, some contemporary theologians express concern that official Church’s long-standing hostility to laughter has led to a religious climate of joylessness: “Even if many priests and ministers admit the need for joy, many religious institutions still seem to find little room for a smile, a joke, laughter, or the occasional measure of silliness” [17, p. 147]. As regards Islam, mass protests against cartoons in Islamic nations and a string of violent attacks by Islamist terrorists against satirical institutions and irreverent jokesters have nurtured the idea that Islam has a basic problem with humour.

By contrast, several scholars working in the sociology and history of humour have argued that eastern religions, especially Hinduism, are particularly accommodating of laughter and that humour even functions as a natural attribute of their religious practices.

The empirical study of almost 800 mostly younger participants, focusing on practicing Christians, Hindus, Muslims, as well as on Atheists and Agnostics evaluates humour appreciation in relation to religious affiliation and specifically studies the response to offensive religious jokes [24]. The evidence provides that religious belief affects the response to jokes on religion, but not jokes on other life manifestations. Religious belief does not prevent people from appreciating humour, not even if this humour is religious in nature, but religion strongly affects how the offensiveness of jokes is experienced.

The proposed project, if successfully implemented, is of some value both for academic circles and for religious leaders, as well as for all interested subjects of communication about religion in the public sphere.

The “conflictness” of humour in media: preliminary observations

In general, when it comes to research object, the humour on religion in media discourse as a factor of conflict seems to be reasonable to divide it into two levels: theoretical and empirical. The theoretical object is the humorous segment of the communicative culture in society in the context of religion. The empirical object consists of humorous content about religion (textual, graphic, audio-visual) in media, texts of interviews with religious leaders, journalists, experts, doctrinal and theological texts about humour, focus group materials, data of statistical and sociological research.

The possible research in this field has consequently theoretical and practical aims. The main theoretical aim is to build a normative model for the representation of the humorous attitude towards religion in media and more broadly in modern culture, based on the principles of dialogue and consensus. The main practical goal is to develop an effective tool (guidelines) for politicians, journalists, cultural and religious leaders with clear demarcation “red flags” line in order to avoid conflicts as it happened in the modern history of Europe (Charlie Hebdo, etc).

To achieve the theoretical aim, it is important to identify the fundamental, dogmatic grounds for the tolerated and non-tolerated humour in various religions (mainly in Christianity, Judaism and Islam) and also to analyse the concepts of laughter culture in a religious context, to differ humour (irony, sarcasm, satire, grotesque, etc.) from blasphemy and defamation of religions. From another side, it seems to be important to explore the main modern media theories and the concept of the mediatization of religion and to discover the normative principles that could form the basis of a model for representing the laughter attitude to religion in the media and in modern culture.

The practical aim presumes the mapping of the areas of conflicts, their main factors and “triggers”, and also to clarify the real mutual expectations of spiritual leaders, journalists, politicians, cultural influencers, precisely describing tolerated and non-tolerated humour in this area.

Basically, the following questions should be addressed and answered:

1. What kind of humour is appropriate and inappropriate in different religious communities (Orthodox, Catholic, Protestant, Islamic, Jewish)?

2. What kind of humour is appropriate and inappropriate in media coverage of religion according to international journalistic standards, local journalistic cultures, ethical norms and personal convictions?

3. To what extent religious and media communities are ready for mutual concessions in order to reach a zone of agreement based on compromise and consensus?

Answers to these questions will give the opportunity to map the “zone of mutual responsibility” and then to elaborate on the formal “pact on humour” signed by journalists and religious leaders.

Both theoretically and practically the situation when a) established in particular religious community implicit norms are adjusted towards the freedom of speech and b) media practitioners try to respect and keep the limits of humour in their discourse on coverage religion is a goal to achieve, and this mission is possible.

Methodologically the proposed research could be based on the functional analysis of humour in different religions, content analysis of media texts containing humour in coverage on religion and in-depth interviews with a) journalists dealing with religious issues; b) religious leaders and officials responsible for media and public relations and c) experts in the conflict resolution. If needed, the focus-group discussion on the appropriate and inappropriate humour in media discourse on religion could also be heuristically promising.

As a project practical outcome, the guidelines for journalists, politicians and public activists and religious communities could be elaborated and published. They should contain: a) the map of risky “minefields” and strictly taboo for making jokes with demarcation lines and the detailed description of sensitive areas that may potentially cause conflicts with different religions (mostly Christianity, Islam and Judaism); b) the media literacy norms and rules for a better understanding of the nature of media coverage of religious life in the context of the freedom of expression and the right of the general public to be informed.

A pilot study conducted by the authors of this paper in Moscow in 2021-2022 (16 in-depth interviews with religious leaders and journalists) showed that the topic of conflict humour in the media is poorly understood and discussed across religions; for many respondents this was the first conversation in this perspective.

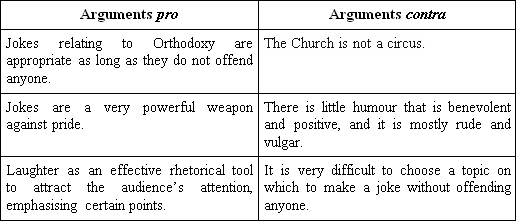

Orthodox humour is widely discussed in Orthodox media [q.v.: 1; 2; 3; 4; 5]. But Orthodox priests and laymen perceive humour about themselves and their religion rather neutrally, in balanced way. Their responses can be summarised in the following table:

Russian Orthodox view on humour in media: pro at contra

Influential Orthodox media (e.g. Radio Vera, Foma magazine) use humour in its various forms. There is a discussion about humour as an acceptable or unacceptable phenomenon (for example, on Spas TV, where Archpriest Andrey Tkachev answered listeners’ questions about acceptable and unacceptable humour) [3]. Also, for example, there are often sections with jokes in profile media. For example, the Yelitsy website has a section entitled “Orthodox humour”, which publishes jokes that are in one way or another related to religion [2].

As for Islam, Russia’s second largest religion by number of believers, respondents stressed that the Quran and Sunnah are the sources for Muslims to form an opinion on any issue that arises.

“Praiseworthy jokes are not accompanied by a violation of Allah's prohibitions, sins or the severing of kinship ties. The jokes that are condemned are those that entail enmity, remove dignity and destroy friendship”, a Muslim mufti told us in an interview. He added that the Prophet forbade any words and actions that degrade someone’s dignity.

Islamic tradition stresses the need for moderation. The restrictions imposed on humour and laughter in Islam are related to two fundamental points: 1) a person as part of society must follow the accepted norms of society and 2) a Muslim believer must observe his duties before God.

In the first case, humour should not bring harm to society and discomfort to other members of society, laughter and fun should not be a problem in interaction with people and in the second case, it is a duty of a person before God: humour should not divert a believer from the proper observance of religious prescriptions. In addition, the believer should not use lies and deception; he should not treat another person disparagingly, ridiculing and mocking him; jokes that may frighten a Muslim are not allowed; jokes on topics that require taking themselves seriously should not be used; humour should be moderate and reasonable and should not override the duties imposed by God and people.

Today, representatives of Islamic communities demonstrate some willingness to engage in dialogue with the media; every year they produce more and more research on the construction of the image of Muslims in the media. In particular, intellectual Muslims several times mentioned in interviews the forum “Islam in a multicultural world”, which is being held in Kazan.

Catholics were more open to interviews about humour in religion than Muslims and Orthodox. Catholics are tolerant of harmless jokes about the Church, the Pope and the Vatican, and even joke willingly themselves.

Catholic priests and laity have cited Pope Francis’ words that Christianity spreads through the joy of disciples, who know they are loved and saved. There are many Catholic forums, for example, there is a rubric on ruscatolic.ru with humour, including self-irony.

In the interview, reference was made to the case of the French Jesuit weekly Études, which published satirical drawings of Charlie Hebdo mocking Catholicism on its website in order to show the importance of the art of caricature in society. A huge array of Catholic memes can be found in social networks groups. These memes are fairly benign in nature and are not provocative or religiously distinctive. As we can see, in general, there is some good and gentle humour in the minds of people of this religion. The objects of humour are not only the Bible, saints, but also God Himself.

As far as Protestants are concerned, they are quite relaxed about humour. Believers and many members of the clergy do not consider jokes to be blasphemous, vulgar or wrong.

In Christian society, there are stereotypes that have been formed about members of the Protestant community. Most of the time they are drawn back to the origin of the religious movement, when Protestantism was considered a heresy. In Western culture, there are many insulting nicknames addressed to Protestants. Their use in the media, even in a jocular form, is not correct.

Jewish respondents noted that in Judaism it is a lot of varied, preferring wordplay, irony and satire, it pokes fun at both religious and secular life. Jewish humour is unique in the sense that its humour is based on making fun of “us” (Jews) rather than of “others”.

One Russian rabbi told us in an interview: “Humour is normal and even good. It is a subtle talent that G-d gave to man as a gift. The Talmud cites such a story. A rabbi asked one of the prophets: Who deserves heaven? And the prophet pointed to two merry men who made sad people laugh”. That is, positive and subtle humour is, from the point of view of the Jewish respondents, normal and even good.

Conclusion: further research perspectives

As for possible directions for further developing the project in a comparative perspective, it seems to be very promising to analyse the religious and ethnic factors in the formation of a sense of humour and culture of laughter in general.

On the one hand, the religious worldview is based on general “normativity”, on the understanding of what is good and what is bad, as well as on a solid and transparent hierarchy of values, of what you can laugh at and what you cannot. From this point of view, the humour of Christians is fundamentally different from the humour of Jews or Muslims.

On the other hand, the empirical observations of intercultural communication show that the laughter culture of ethnic groups is different, even if they profess the same religion, which influenced the formation of the laughter culture. For example, the sense of humour among Catholics in Ireland, Italy, Poland and the Philippines will be different, and this is where the ethnic factor comes into play: English humour, French humour, Bulgarian humour are widely known.

Obviously, it is most difficult to find differences in different countries in the humour of Jews, where ethnic and religious, with rare exceptions, represent a fundamental unity, which only in recent centuries has been eroded due to processes of active migration and secularization.

From a wider perspective, this important area could become essential for further research.

Bibliography:

1. Островская Е.А. Медиатизация Православия – это возможно? // Мониторинг общественного мнения: экономические и социальные перемены. 2019. № 5 (153). С. 300-319.

2. Православный юмор [Web resource] // Елицы. Медиа. 15.07.2017. URL: https://bit.ly/3eOIL5f (дата обращения: 15.10.2022).

3. Православный юмор: шутить или не шутить? [Web resource] // Православная жизнь. 23.08.2015. URL: https://bit.ly/3THMjFl (reference date: 15.10.2022).

4. «Смеяться, право, не грешно?» [Web resource] // Вода живая. Санкт-Петербургский церковный вестник. 2012. № 10. URL: https://bit.ly/3VExvcl (reference date: 15.10.2022).

5. Юмор с человеческим лицом [Web resource] // Правмир. 28.07.2010. URL: https://bit.ly/3TJjjNv (reference date: 15.10.2022).

6. Arbuckle G.A. Laughing with God: Humor, culture and transformation. Collegeville, NM: Liturgical Press. 2008. XVIII, 187 p.

7. Berger P.L. Redeeming laughter: The comic dimension of human experience. Berlin: De Gruyter. 1997. XVII, 215 p.

8. Davies C., Kuipers G., Lewis P. et al. // The Muhammad cartoons and humour research: A collection of essay // Humour – International Journal of Humour Research. 2008. Vol. 21. No. 1. P. 1-46.

9. Davies C. The Protestant ethic and the comic spirit of capitalism // Jokes and their Relation to Society / Ed. by V. Raskin, W. Ruch. Berlin; New York: Mouton de Gruyter, 1997. P. 43-62.

10. France honours ‘quiet hero’ teacher killed for showing Prophet Mohammed cartoons [Web resource] // France24.com. 15.10.2017. URL: https://bit.ly/3THQiBt (reference date: 15.10.2022).

11. Geybels H., van Herck W. Humour and religion: Challenges and ambiguities. London: Continuum. 2011. XII, 272 p.

12. Hyers M.C. Zen and the comic spirit. London: Rider and Co. 1974. 192 p.

13. Jonsson J. Humour and Irony in the New Testament, illuminated by parallels in Talmud and Midrash. Reykjavik: Bókautgáfa Menningarsjóðs. 1965, 299 s.

14. Khan Y. Does Islam have a sense of humour? [Web resource] // BBC News. 20.11.2007. URL: https://bbc.in/3EZS1xW (reference date: 15.10.2022).

15. Kuschel K.J. Laughter: A theological essay. London: SCM Press. 1994. XXI, 150 p.

16. Le Goff J., Truong N. Une histoire du corps au Moyen âge. Paris: Liana Levi. 231 p.

17. Martin J.S. Between heaven and mirth: Why joy, humor, and laughter are at the heart of the spiritual life. New York: Harper Collins. 2011. 272 p.

18. Merritt J. Why Christians need to laugh at themselves [Web resource] // The Atlantic. 12.12.2015. URL: https://bit.ly/3SlbADZ (reference date: 15.10.2022).

19. Metz J.B., Jossua J.-P. Theology of joy. New York: Herder and Herder, 1974. 158 p.

20. Minsk profane caricature targets Catholic society in Belarus [Web resource] // Tvpworld.com. 07.09.2021. URL: https://bit.ly/3SiRCKg (reference date: 15.10.2022).

21. Morreall J. Comedy, tragedy, and religion. New York: State University of New York Press. 1999. 188 p.

22. Raymond C.W. Race/ethnicity, religion and stereotypes: Disparagement humour and identity construction in the college fraternity // Jugendsprachen: Stilisierungen, Identitaten, mediale Ressourcen / Hrsg. H. Kotthoff, C. Mertzlufft. Bern: Peter Lang Gmbh, 2014. S. 95-113.

23. Saroglou V. Religion and sense of humour: An a priori incompatibility? Theoretical considerations from a psychological perspective // Humour: International Journal of Humour Research 15(2), 2002, pp. 191-214.

24. Schweizer B., Ott K.H. Laughter and faith: Do practicing Christians and atheists have different senses of humour? // Humour – International Journal of Humour Research. 2016. Vol. 29. No. 3. P. 413-438.

25. Ziv A. National Styles of Humour. New York: Greenwood Press. 1988. 242 p.

Data about the authors:

Khrul Anastasiia – Master of Cultural Studies, Doctoral Candidate of Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński University (Warsaw, Poland).

Khroul Victor – Doctor of Philological Sciences, Visiting Researcher at Catholic University in Ružomberok (Ružomberok, Slovakia).

Сведения об авторах:

Хруль Анастасия – магистр культурологии, докторант Университета кардинала Стефана Вышинского (Варшава, Польша).

Хруль Виктор – приглашенный исследователь Католического университета в Ружомбероке (Ружомберок, Словакия).

E-mail: cavesegnitiam@gmail.com.

E-mail: victor.khroul@gmail.com.