Khroul V. Digital games, virtual reality and post‐truth concept

УДК 111.1:070:004.42

DIGITAL GAMES, VIRTUAL REALITY

AND POST‐TRUTH CONCEPT

Khroul V.

The paper examines digital games, labelled by some scholars as “the avant‐garde of contemporary audio-visual culture” and “the mass media of the 21st century”, in the perspective of recent concept of ‘post-truth’. The “relativisation” of truth and the blurring of the boundaries between truth and falsehood in the digitalized public sphere are nowadays positioned in media discourse and academic literature as a normal historical process. The author proposes to subject correctness and heuristic value of the ‘post-truth’ notion to careful critical analysis and suggests that ‘post-truth’ makes a fundamentally important essential substitution: truth in it is stripped of its absolute status and placed in the same line with things temporary, finite, conventional as post-communism, post-totalitarianism, post-modernism, post-secularism, etc. Since ‘post-truth’ contains not only a logical, but also an ontological error, the author calls not to analyse digital games in the context of ‘post-truth’ and use traditional frameworks based on clear true-false methodological matrix.

Keywords: digital games, post-truth, values, digitalization, relativism.

ЦИФРОВЫЕ ИГРЫ, ВИРТУАЛЬНАЯ РЕАЛЬНОСТЬ

И КОНЦЕПЦИЯ ПОСТПРАВДЫ

Хруль В.

В статье рассматриваются цифровые игры, которые некоторые ученые называют «авангардом современной аудиовизуальной культуры» и «средствами массовой информации XXI века», в контексте современной концепции «постправды». «Релятивизация» истины и размывание границ между истиной и ложью в цифровой публичной сфере сегодня рассматриваются в медиадискурсе и академической литературе как нормальный исторический процесс. Автор предлагает подвергнуть корректность и эвристическую ценность понятия «постправда» тщательному критическому анализу. Предполагается, что «постправда» совершает принципиально важную существенную замену: истина в ней лишается своего абсолютного статуса и ставится в один ряд с временными, конечными, конвенциональными вещами – посткоммунизмом, посттоталитаризмом, постмодернизмом, постсекуляризмом и т.д. Поскольку «постправда» содержит не только логическую, но и онтологическую ошибку, автор призывает не анализировать цифровые игры в контексте «постправды» и использовать традиционные рамки, основанные на четкой методологической матрице «истина-ложь».

Ключевые слова: цифровые игры, постправда, ценности, цифровизация, релятивизм.

Funded by the EU NextGenerationEU through the Recovery and Resilience Plan for Slovakia under the project No. 09I03-03-V01-00088.

Recently digital games have been ‘awarded’ with very impressive labels: they have been called the “the avant‐garde of contemporary audio-visual culture” and “the mass media of the 21st century”. The 21st century is considered by some experts to be the “age of games”. All this prominent evaluations of the digital gaming call the academia to critical rethinking of the phenomena of digital games and virtual reality from the perspective of values and truth.

Homo ludens in digital age

Gaming itself – neutral by its nature – does not put homo ludens [q.v.: 11] into psychological problems. Huizinga argues that playing games is a necessary element in the generation of human culture. He analyses games through the concept of the “magic circle,” in which the rules and role of everyday practices are suspended and replaced with games. Homo ludens is out of risk until he a) is free, b) differs gaming reality from reality itself and c) is not addicted to games. But it is not enough ontologically, because another factor in this context is important: homo ludens is homo sapiens until the games are based on positive values. Therefore it seems to be impossible to conduct the functional analysis of digital games and virtual reality outside the normative approach based on the differentiation of good and bad, true and false.

The process of digitalization technologically is neutral, ambivalent, but regarding the content it has several important consequences: 1) simplification, 2) ‘twitterization’, 3) ‘iconization’. These three factors reduce the density of the reality to low resolution, make the picture more simple and less nuanced, less colourful, less halftoned. Another three consequences are the result of the digital impact on the audience: 1) atomization, 2) fragmentation and 3) time limitation. Therefore our hypothesis (partly proved by observations and empirical research) is the following: the more digital ‐ the more simple, poor, primitive, fast communication is in general.

Widely expanding digital gaming produces in this context several 'warning bells' about the following threats:

Manipulation of reality: blurring the line between what is real and what is simulated;

Manipulation of identity: VR avatars and identities can be manipulated;

Echo chambers and filter bubbles limit exposure to alternative viewpoints and diverse sources of information;

Confirmation bias: blocking critical thinking.

And all these warning bells should be taken seriously not only by researchers, but also by decision makers while addressing digital gaming.

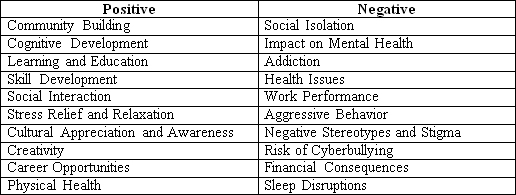

We have asked AI ChatGPT about positive and negative impacts of digital games. The answers you can find in the table Impact of digital games.

Table evidently shows that gaming could easily lead to symmetrical positive-negative consequences: community building – social isolation; cognitive development – impact on mental health; stress relief and relaxation – aggressive behaviour, etc.

It’s essential for individuals to be mindful of their gaming habits and strive for a balanced approach to gaming that prioritizes overall well‐being and healthy lifestyle choices. Developers and content creators must consider the potential consequences of creating and disseminating VR content that perpetuates falsehoods, misinformation, or harmful ideologies. Parents, educators, religious leaders and policymakers also play a crucial role in promoting responsible gaming practices and neutralize potential negative impacts which are based mostly on disbalanced true-false scale in digital gaming [3].

Post-truth: heuristic value and ontological essence

‘Post‐truth’ (both as a vivid metaphor in journalistic discourse and a scientific term) arrived within and along the digitalization.

The heuristic value of each new notion introduced into academic discourse – regardless of its popularity – determines to a large extent its future. Therefore, a critical analysis of new terminology is a crucial task of scholarly dialogue. In this paper, we will attempt to examine the history and extent of the use of the word ‘post-truth’ in major media, as well as critically analyse its use in academic publications, paying particular attention to two questions: 1) What heuristic value does this term represent? 2) What is its ontological essence?

The neologism post-truth was first used in 1992 by Steve Tesich, an American of Serbian origin, in his publicist work on the U.S. war in the Persian Gulf [16]. And he evidently used this word as a new impressive journalistic metaphor.

The first scholarly attempt to make sense of the new concept was an article in the 1996 reprint of the Oxford Dictionary. The word post-truth was defined in the English Dictionary as “relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief”. The term was further popularized in Ralph Keyes’ book “The post-truth era: dishonesty and deception in contemporary life”[13]. According to Keyes, society is entering the post-truth era as lies begin to dominate every day and political life. He also writes about the so-called “technical deception” that allows lying without consequences as a result of the anonymity of the Internet.

The term ‘post-truth’ has since been used to describe a communication situation in which truth is no longer fundamentally important. Post-truth began to refer to the information flow, which is intentionally constructed in modern society with the help of the media and other channels to create a virtual reality in order to manipulate the public consciousness. In the era of post-truth, objective facts are less important in shaping public opinion than appealing to emotions and personal beliefs, meaning that people believe what they want to believe and are more willing to remain captive to their stereotypes and biases instead of trusting numbers and concrete data.

As a result, there is more information, but it is less and less verified. Information is no longer valuable in and of itself; it is the attention paid to it and the emotional context that is more important. According to Farkas and Schou, the world is entering a post-truth era largely due to the proliferation of social media and online platforms, where people receive often deliberately distorted information about world events, as the fragmentation of news sources creates a situation where lies, gossip, and rumours online can very quickly substitute for truth [q.v.: 7]. Rationality no longer prevails in the analysis and evaluation of information, the role of emotion in the perception of not only information, but reality itself is increasing. Facts, evidence, and data as objective reflections of events are being equated with opinions, reviews, and rumours, and the measure of truth becomes the individual with his or her personal perception and the “information bubble”.

The world today faces a profound crisis of disinformation: false and unverified information spreads like a virus, creating problems for society, primarily due to a devaluation of trust in fact. In other words, the usual appeal to the minds of fellow citizens is becoming less and less effective. Freedom of speech in modern society is ensured to a large extent by an unprecedented leap in the development of the media. But it is modern media, in turn, that create the preconditions for the crisis of this freedom, because it becomes the ground for the spread of lies. Many attribute the cause of the advent of the post-truth era to fake news. The existence of lies in social life and the media is not a new phenomenon, but the situation is getting worse because information can now spread with a speed and reach never seen before.

Sensational messages and vivid terms, which seem to bring a new interpretation of events, phenomena and processes, are being rapidly spread claiming to offer an innovative language to describe a new reality mankind faces. In general, the media surge of post-truth (hereinafter this term will be used without quotation marks) is associated with the difficulty of distinguishing between truth and lies, about which A. Bystritsky recently wrote: “We are talking about fake news, information confusion and cognitive dissonance, which a large part of the population experiences because of the inability to distinguish truth from lies” [2, p. 133].

Post-truth has been perceived in recent years as an axiom, a given, a commonplace, and even a truism, but not subject to question or critical analysis. Unfortunately, its widespread use in publications is not supported by arguments in favour of its special heuristic value.

Post-truth has come to be called a state of affairs in which boring truth is replaced by spectacular lies: “All these phenomena and many others point to a new political era or paradigm: we are facing a post-truth society or an era of post-facts, in which Truth and Reason are displaced by alternative facts and individual inner feelings” [7, p. 2]. Today, post-truth describes an era of mass communication development in which truth is no longer fundamentally important. Post-truth is an information flow that is intentionally constructed in modern society through media and other channels to create a virtual, different reality [q.v.: 11].

While reading papers about post-truth, one gets the feeling that political scientists, sociologists, and publicists are competing in the use of a fashionable construct. However, if we stop and look around, we must admit that there are questions about the term. Has there really been a global tectonic shift in attitudes toward truth and the foundations of journalism? Are we really, as a number of academic papers and journalistic articles have argued, living in an “age of post-facts” and in a “post-truth society”, where truth and causality have been replaced by individual feelings and sympathies? Are these processes historically determined and irreversible?

Absolute or relative?

At first glance, the symptoms of “relativisation” and devaluation of truth are visible: audiences have become less trusting of scientific evidence, preferring conspiracy interpretations (e.g. about climate change), rigorous medical diagnoses are losing popularity to recipes from the Internet, and quality journalism based on fact checking is drowning in a flood of disinformation produced by “fake news farms”, “troll factories” and cleverly wielding bots online.

Post-truth worlds are commonly seen as discursive formations created, disseminated and prevalent in the information space. Their internal logic and hidden normative preconditions are based on the relativization of truth and actually contradict the classical notions of journalism. This new “non-Euclidean geometry” is ontologically questionable. The fact that the public sphere faces a profound “crisis of facts” [q.v.: 5] does not derive from the need to accept post-truth theory unconditionally and uncritically as an irrefutable given.

In fact, the idea of a post-truth era contains an underlying nostalgia for the era of truth. The very idea of the post-truth era also fails to deny that the default information order is based on the notion of the essential absoluteness of truth. Not even for a moment can we imagine, for example, that in the binary system “0” and “1” have reversed values: the relativization of mathematics and informatics leads to a chaos of uncertainty. And in this sense, the world of facts is also “binary”, unambiguous. Of course, the same cannot be said of the world of interpretations, but journalism is built primarily on facts, and interpretations are the prerogative not only of journalists and experts, but also of the audience itself. Consequently, the assumption that the possibility of different interpretations of a predominantly emotional nature proves that the relativity of truth as such is questionable.

Nevertheless, the major media outlets in Europe and the United States condemn the new era of disinformation, publishing numerous notes, articles and commentaries on the post-truth era. There is no shortage of commentators and intellectuals denouncing the onslaught of fake news and post-truth and publishing books with catchy titles: “Post-truth: how bullshit conquered the world” [1]; “Post-truth: why we have reached peak bullshit and what we can do about it”[6]; “Post-truth: the new war on truth and how to fight back” [4]; “The death of truth: notes on falsehood in the Age of Trump” [12].

There is also a growing analytical reflection in academia on the uncontrolled and uncritical flow of lies that audiences perceive. Researchers willingly place the word post-truth on the title page of their papers, introducing it into scholarly usage as a term of heuristic and interpretive value, but they do not subject post-truth to a thorough terminological analysis: “Post-truth”[14];“Post-truth: knowledge as a power game”[8];“Everything is permitted, restrictions still apply: a psychoanalytic perspective on social dislocation, narcissism, and post truth” [17];“Fake news: falsehood, fabrication and fantasy in journalism”[15]etc.

The analysis of the use of the word post-truth in a global context in Factiva global news monitoring and search engine confirms the extent of the “fascination” with this construct. A sharp media spike in the use of the word occurred from 2016 to 2018 (Brexit in the United Kingdom and Trump’s election in the United States), but even after the peak, the use of the term has not returned to the level of 2014, meaning that the post-truth usage has expanded and again shows an upward trend.

In terms of languages of use, according to Factiva, Spanish and English are firmly in the lead, with Spanish (36.5%) already ahead of English (33.2%) by now. French (3.4%) and German (1.6%) are followed by Portuguese (5.2%) and Chinese (3.8%), and Russian is 1.4% of all post-truth uses. This distribution by language generally corresponds to the general proportions of resources in these languages in the general body of texts, indicating a more or less equal penetration of post-truth in the global information discourse.

Temporary or eternal?

Post-truth has changed sources and forms, but it has existed and perhaps dominated in all times: we can easily find post-truth as we understand it today in the ancient world, in the Middle Ages and even in the Enlightenment, much less in contemporary times. From the rhetorical techniques of the sophists to contemporary propaganda discourse, information that resonates with the emotional expectations of the audience and corresponds to the political goals of the communicator has always been valuable.

A legitimate question arises: Is a new term really necessary if it describes a reality that existed before? What is its heuristic value? Does all of the above give post-truth a pass into scientific discourse? Is the introduction of the term sufficiently justified? From our point of view, the answer is “no”, and we will try to prove it below.

Even a primary terminological questioning of post-truth reveals a logical, philological and even ontological error in this word, which strangely remains unarticulated in academic publications, much less in journalistic texts.

Thus, even the most superficial attempt to deconstruct the term post-truth exposes a fundamentally important essential substitution: truth with the prefix “post” loses its absolute status and is placed on a par with things temporal, finite, relational, conventional. The prefix “post” is correctly and adequately used in such words as post-communism, post-totalitarianism, post-modernism, post-secularism. But it is impossible to call it correct in the word post-truth? The words communism, totalitarianism, modernism, and secularism have an obvious temporal aspect, which is inapplicable to truth. It is an error.

As a consequence of this error, the prefix “post” means not only “after”, but also ‘beyond” in the sense that truth is no longer relevant. The relativization of truth, the blurring of the boundaries between truth and falsehood are thus positioned as a normal historical process: there was one truth, it ended, and now there are many and all are different...

Progress or crisis?

Along with the crisis of traditional media, there has been a decline in trust in journalistic activities and journalism as a whole. The decline in trust in the media automatically leads to an uninformed audience, and people become more vulnerable to extremist messages and false news. “The most important thing in a functional society is a well-informed public. What we have now is not only uninformed but also misinformed masses” J. Farkas and J. Schou noted [7, p. 60]. The current media landscape makes it impossible to adequately select sources because of their sheer number, which creates information or misinformation overload. Therefore, according to Farkas and Schou, quality journalism is threatened by fake news and bots, and “the traditional guardians of truth – editors and journalists – have lost their monopoly on truth” [7, p. 60]. Post-truth discourse sometimes is defined as a discourse in which “truthiness” is more important than truth [14, p. 596].

Indeed, media audiences are strongly emotionally attached to their deeply held beliefs. There is a valid reason for this phenomenon: such beliefs may have been internalized by the psyche while the child was still being raised by parents, but also because of other people who had an influence on the formation of the personality: teachers, religious and cultural leaders, colleagues. Throughout the period of personality formation, all that was shaped by life experience had to provide systematic reinforcement of learned cognitive attitudes, including political preferences, ethical and moral standards, and a picture of the world as a whole.

In our opinion, the viral spread of the word post-truth could have significant consequences for modern journalism, calling into question the ontological essence of this profession. Nick Davies, an experienced and uncompromising British journalist and author of the popular book “Flat Earth news”, expressed it very precisely and clearly: “The main purpose of a journalist is to try to tell the truth about important things to the audience” [5, p. 21]. Truth is the main category of this definition, and if it ceases to be taken seriously, if it is interpreted relativistically, then the profession of journalism itself essentially loses its foundation.

Journalism – as well as science, religion, law – is not sentenced by its nature to capitulate to lies. But every use of the term post-truth in media discourse, in the sense of a new information reality in which truth is relative and unimportant, is precisely, in our view, a step toward surrender. And this surrender will mean a systemic shift, an aberration in the global online information space, when the picture of the world is distorted by the essential substitution of concepts and its incorrect description.

Conclusion

Digital gaming seems to be a very easy target for the post-truth expansion into the 21th century lifestyle and modus operandi. Nevertheless, technology itself has never been ontologically decisive in the history of mankind. Human beings – only and exclusively – made decisions on what is true and what is false, what is good and what is bad, and made choices in favour or against. So this paper, full of concerns, is not pessimistic. In contrary, it is rather optimistic and based on the presupposition that good will is located in the core of human nature...

The German philosopher and rationality apologist Jürgen Habermas emphasized that “democracy without truth can no longer be democracy” [10, p. 18]. In an era of viral proliferation of lies, there remain a number of social institutions that can be called the “last bastions” of truth, where, contrary to the rules of politics, truth and veracity have always remained the ultimate yardstick for evaluating speeches and efforts. These are the spaces of honest science, systematically directed toward the search for truth; the judiciary, whose procedures aim to make just decisions; and religious communities, for whom truth is an absolute. These subsystems of society increase the chances of truth prevailing in the public sphere, even if their present state seems deplorable to us.

The concept of post-truth, by denoting complex and ambiguous processes, even if it is accompanied by negative connotations, legitimizes in public opinion and scientific discourse a state of affairs that is ontologically impossible in those frames of reference where absolutes are supposed to exist, including the standard system of contemporary journalism, which implies the distinction between the true and the false. In advocating a critical attitude to the term post-truth, we are not trying to “undo” negative processes in the global information space. We propose to describe them in other terms - ontologically acceptable, adequate and heuristically valuable.

Today, in three major areas of study within ethics – (1) meta-ethics, concerning the theoretical meaning and reference of moral propositions, and how their truth values can be determined, (2) normative ethics, concerning the practical means of determining a moral course of action and (3) applied ethics, concerning what a person is obligated to do in a specific situation – meta-ethics, referring to truth, is becoming more and more important. Values play an integral part in ethics because they can be understood as the goal as well as outcomes of norms that are given to reach the “good” [9, p. 84].

And – despite of tremendous obstacles in modern life – true values could and should become the background of digital gaming.

Bibliography:

1. Ball J. Post-truth: How bullshit conquered the world. London: Biteback Publishing, 2018. 306 p.

2. Bystritskiy A. Universal Dead-end in a Global Wormhole. The Need to Regulate Modern Communications // Baku Dialogues. 2021. Vol. 4. No 2. P. 132-143.

3. Campbell H. Grieve G. Playing with Religion in Digital Games. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2014. IX, 301 p.

4. d’Ancona M. Post-truth: The new war on truth and how to fight back. London: Ebury Press, 2017. 167 p.

5. Davies N. Flat Earth news: an award-winning reporter exposes falsehood, distortion and propaganda in the global media. London: Vintage Digital, 2011. 432 p.

6. Davis E. Post-truth: Why we have reached peak bullshit and what we can do about it. London: Little, Brown, 2017. XX, 347 p.

7. Farkas J., Schou J. Post-truth, fake news and democracy: Mapping thepolitics of falsehood. New York: Routledge, 2020. XI, 166 p.

8. Fuller S. Post-truth: Knowledge as a power game. London: Anthem Press, 2018. 220 p.

9. Grieve G.P., Radde-Antweiler K., Zeiler X. Paradise lost. Value formations as an analytical concept for the study of gamevironments // Gamevironments. 2020. Vol. 12. P. 77-113.

10. Habermas J. (2006). Religion in the public sphere // European Journal of Philosophy. 2006. Vol. 14. No 1. P. 10-25.

11. Huizinga J. Homo ludens: A study of the play element in culture. London: Routledge & K. Paul, 1949. 220 p.

12. Kakutani M. The death of truth: Notes on falsehood in the age of Trump. New York: Tim Duggans Books, 2018. 208 p.

13. Keyes R. The Post-truth era: Dishonesty and deception in contemporary life. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2004. VIII, 312 p.

14. Lakoff R. The hollow man: Donald Trump, populism, and post-truth politics // Journal of Language & Politics, 2017. Vol. 16. No 4. P. 595-606.

15. McNair B. Fake news: Falsehood, fabrication and fantasy in journalism. London: Routledge, 2018. 116 p.

16. Tesich S. A government of lies [Web resource] // The Free Library. 2025. URL: https://goo.su/37GT8bX (reference date: 09.10.2025).

17. Thurston I. Everything is permitted, restrictions still apply: A psychoanalytic perspective on social dislocation, narcissism, and post-truth. London: Routledge, 2018. XX, 191 p.

Data about the author:

Khroul Victor – Doctor of Philological Sciences, Visiting Researcher at Catholic University in Ružomberok (Ružomberok, Slovakia).

Сведения об авторе:

Хруль Виктор – приглашенный исследователь Католического университета в Ружомбероке (Ружомберок, Словакия).

E-mail: victor.khroul@gmail.com.